How pancreatic cancer spreads after surgery

COLD SPRING HARBOR, N.Y., May 17, 2018 /PRNewswire/ -- Scientists at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) have solved a mystery about how pancreatic cancer spreads following surgery in patients whose tumor is successfully removed.

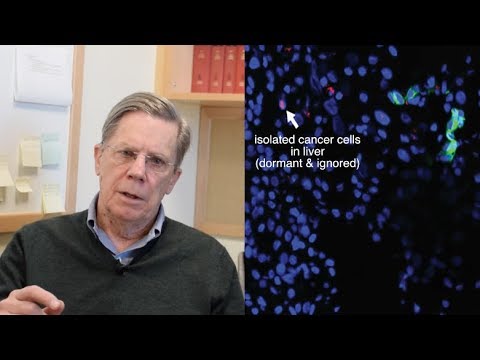

After surgery, patients' typically experience a two-week period during which their immune system is depleted due to a surge in post-operative stress hormone (cortisol) levels. With killer T-cell levels sagging, isolated, dormant cancer cells that have already traveled to the liver and possibly other organs via the bloodstream begin to grow or metastasize.

This post-operative period, suggests CSHL Professor Douglas Fearon, "offers a window during which efforts might be made to keep cortisol levels down and T cells strong so the patient's own immune system can kill the cancer cells that have made their way to other parts of the body but until this point have been dormant."

Surgery is usually not an option for pancreas cancer patients, since most are diagnosed after the primary tumor has metastasized. This explains why only 8 percent of those diagnosed are still alive after 5 years. But doctors have been puzzled by the poor outcome in patients who should do better: the minority whose tumor seems confined to the pancreas at the time of diagnosis, and qualify for surgery. In many such patients, the liver, inspected during the operation, appears cancer-free. Yet within two years, most of these patients develop lethal metastatic cancer, often in the liver.

Today in Science a team led by Fearon and Dr. Arnaud Pommier, explains that dormant cancer cells are already in the liver well before patients have their primary tumor removed. They are likely carried there by the bloodstream, having been shed by the primary tumor. Fearon estimates that in a typical patient, 14 million cancer cells pass through the liver daily.

The immune system can kill most of the cancer cells deposited in the liver, but often it isn't completely effective. Fearon and others have discovered in recent years how the immune system can be tricked or hijacked by cancer cells. The new discovery is one example.

The immune system seeks out and destroys cancer cells by sensing proteins called MHC1 and CK19 that are present on the outer membrane of the cancer cells. Fearon's team found that dormant cancer cells in the liver of pancreatic cancer patients don't express these proteins, so killer T cells can't find them. In situations like post-operative surgical stress, where T cells in the liver are depleted, the dormant cancer cells begin expressing MHC1 and CK19 surface markers again and divide, becoming seeds of metastatic lesions.

About Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory

Founded in 1890, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory has shaped contemporary biomedical research and education with programs in cancer, neuroscience, plant biology and quantitative biology. Home to eight Nobel Prize winners, the private, not-for-profit Laboratory employs 1,100 people including 600 scientists, students and technicians. For more information, visit www.cshl.edu

SOURCE Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory

Share this article